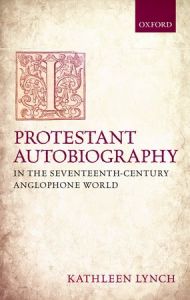

Kathleen Lynch’s Protestant Autobiography in the Seventeenth-Century Anglophone World, published by Oxford University Press earlier this year, is a major new study of early modern spiritual autobiography, with a particular emphasis upon the testimonies collected together, discussed, and laid out in print by members of England’s and America’s gathered churches in the mid-seventeenth century.

In her opening chapter, Lynch offers a new take on perhaps the most influential conversion narrative in the early modern world: a tale of a turn to Christianity that took place more than a thousand years earlier. The conversion of St Augustine was repeated in sermons and religious tracts, and formed a compelling subject for numerous artists.

A historiated initial from a medieval manuscript, showing St Augustine as Bishop of Hippo. University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft Library, BANC MS UCB 002.

Lynch looks closely at the earliest translations of Augustine into English, taking as her starting point the first printed English edition of the Confessions. This fat, squat volume was translated by Tobie Matthew, the Catholic son of York’s very Protestant Archbishop, whose separate manuscript account of his own conversion is, Lynch suggests, highly ‘revealing of the strategies of confessional truth-telling’. The Confessions was printed in St Omer (now in northern France, but then part of the Spanish Netherlands), and smuggled into England for Catholic readers. The text was soon adopted by Protestants as well, who stripped away Matthews’ polemical preface and offered a rather different Augustine to readers.

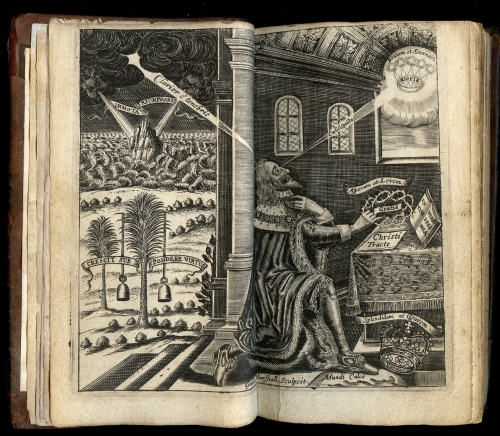

Examining the ways in which both Protestants and Catholics presented the former Bishop of Hippo in print, not least through two different frontispiece engravings, Lynch argues that the books are ’emblematic of Augustine’s divided confessional reputation’ (43), and offer ‘two different views on the authority of writing’ (46). In William Watt’s ‘solidly Protestant edition’ of 1631 (below), we see ‘the inimitable core of conversion — its utter dependence on an unforeseen grace’ (43), with the biblical passage that converted Augustine now oriented towards the reader, encouraging her or him to follow the saint’s lead. In contrast, the Catholic edition of 1638 shows us Augustine as the Church father and source of centuries of authority and tradition, ‘dressed in priestly robes and wear[ing] the bishop’s mitre’ (46).

Lynch suggests that these two images are emblematic of a tension between the first-person testimony of belief and salvation (writing as an expression of self), and the massive authority of the scriptures (writing which directs the self). Readers of Augustine, Lynch reports, possessed ‘a deep readerly skepticism about the independent authority of an autobiographical text’ (47). It is the struggle (often collective rather than individual) to forge an authoritative voice, and to establish the self as a source of credible experience and influence, that forms the subject of Lynch’s book.

The famous engraving of John Donne dressed in his own shroud to prepare for death. Martin Droeshout, line engraving, 1633, NPG D25948. (c) National Portrait Gallery, London.

In the first chapter, John Donne, a convert from Catholicism, appears as a figure who was innately suspicious of claims to individual authority, and who, Lynch argues, consistently refused to follow in Augustine’s footsteps and tell the story of his own conversion. Donne’s Pseudo-Martyr, according to Lynch, ‘bespeaks a converted self while refusing to narrate a conversion’ (51). Donne, Lynch suggests, refused to present his religious affiliation as more important, or more relevant, than, his political affiliation. What matters for Donne, as part of his attempt to forge a broad and unified Church, is his service to the king and state, not his individual experiences.

EXPERIENCES

Lynch’s second chapter introduces, and analyses, the key term of ‘experiment’ (experience) through a reading of the complex case of Sara Wight, a prophesying convert whose despair and salvation were performed before a collection of witnesses linked to the Baptist church of Henry Jessey. Jessey’s account of Wight’s experiences is productively juxtaposed with a very different quasi-spiritual autobiography: Charles I’s wildly popular Eikon Basilike — a text which, as Lynch notes, got the ending most conversion narratives could only aspire to in the celebrated ‘good death’ of its subject shortly after publication.

The frontispiece to Eikon Basilike (1649). Compare this depiction of Charles to the figure of Augustine in the Confessions frontispiece above.

One of the most important things to emerge from this chapter is the extent to which spiritual accounts of the self were communal productions, put together by authors but also by witnesses and communities which included author-editors (Jessey for Wight, and John Gauden, his chaplain, for Charles), as well as members of the publishing trade, whose own religious commitments emerged in their decisions to print or finance particular publications.

The conversion narrative or spiritual testimony was central to the identity, achievements, and proselytising of the nonconformist Christians who are the subject of Lynch’s final three chapters. To become a full member of the congregation a worshipper had to testify to his or her previous sins and wickedness, and tell a convincing story about how he or she had overcome despair through God’s mercy. Each worshipper sought to find a verse from the Bible that was particularly applicable to his or her own experiences, and which they could reflect upon and hold up as part of their personal testimony. John Bunyan, perhaps the most famous convert in this tradition, struggled unsuccessfully to find a verse fit for his purposes for most of his life.

Bunyan is the subject of Lynch’s fourth chapter, where Grace Abounding, his spiritual autobiography, is contrasted in provocative ways with the rather less fortunate narrative of Agnes Beaumont (a story which, Lynch suggests, ‘exposes the gendered limits of who got to tell their story of persecution in public’).

This archetypal convert is, Lynch suggests, more usual than we might think in his ongoing crises and recurring fits of despair: Lynch opens her book with the case of Richard Norwood, one of the earlist settlers of Bermuda (he arrived in 1631), and a telling example of a separatist who engaged in a lengthy and ‘restless search for spiritual consolation’ (2). Norwood’s search, along with the other stories charted in this book, suggests how important the idea of ongoing struggle is to Protestant conversion narratives, and complicates existing accounts which argue that Protestant autobiographies represent the beginnings of ideas about selfhood and identity as secure and reliable categories.

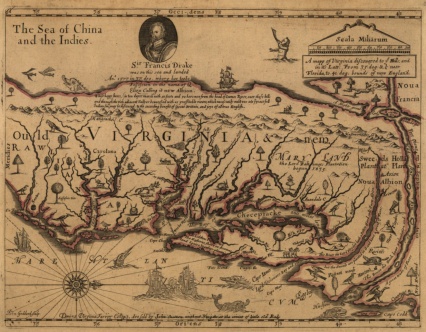

Map of the Somers Isles (Bermuda) by John Speed (1676 edition), based on an engraving by Richard Norwood.

Worshippers’ testimonies were widely discussed and sometimes published in collections of ‘experiences’ designed to further the spread and influence of particular ministers and congregations, or to testify to the (partial) successes of American colonists in managing their own religious affairs and converting the indigenous peoples they encountered in the Americas. This makes spiritual ‘experiences’ unusual — and thought-provoking — as autobiographical texts.

Lynch points out that in 1653, three different collections of spiritual experiences were published, Vavasor Powell’s Spiritual Experiences of sundry Beleevers, a collection of testimonies from ‘independently gathered churches in London’, John Rogers’ Ohel or Beth-shemesh. A Tabernacle for the Sun, which featured testimonies made in Cromwellian Ireland, and Tears of Repentance, a ‘compilation of reports and letters from the New England missionaries John Eliot and Thomas Mayhew [which] included the confessions of faith delivered by nineteen members of a Massachusetts tribe who were in the process of being gathered into a church by Eliot’ (155).

Individually, each of these texts speaks to the experiences of a specific group of people in a tighly-defined geographical, religious, and political situation. Indeed, Lynch notes, they present ‘for virtually the first time in print the new public voices of women, lower classes, ordinary citizens, and the laity’, as well as — though in highly mediated forms — native Americans. Published close together in London, however, the books were transformed, and became, Lynch argues, ‘a virtual assembly of the elect, poised for their millenial opportunity’ (21). The circumstances of print and publication transformed the experiences of these believers, and made them part of a larger, compelling narrative of national and universal salvation.

THE GATHERED CHURCHES AND THE ATLANTIC WORLD

The gathered churches, whose history stretched back to the separatist movements of the 1570s, were given a new force and freedom by Oliver Cromwell’s abolition of the Act of Uniformity in 1650. Before that, English Christians were required to attend their local Parish church and could face stiff fines or punishment if they refused, whether they did so to preserve their Catholic faith (recusancy) or to attend what they saw as a more inspiring or moving service elsewhere (a practice some contemporaries termed ‘sermon-gadding’).

Those who attended gathered churches or congregations believed that the Church on earth should not be defined by geographical circumstance, but made up of groups of like-minded Christians, inspired to come together to worship God. For some Puritans, especially in the early to middle years of the seventeenth century, the colonial settlements of America offered a ‘new world’ in which independent, congregational Churches might thrive.

A mapp of Virginia discovered to ye hills (London, c. 1667), the fifth edition, based on the manuscript map of John Farrer.

In Protestant Autobiography,Lynch suggests that we need to understand ‘the full extent of the development of the Protestant conversion narrative as a circum-Atlantic phenomen’ (122). By uncovering and analysing conversion accounts from New as well as old England, her book makes an important contribution to the history of the Atlantic world (a term historians use to indicate the links and connections between countries on the Atlantic Rim), and shows persuasively the brisk traffic of news, narratives and ideas between England and her colonies.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY IN PRINT

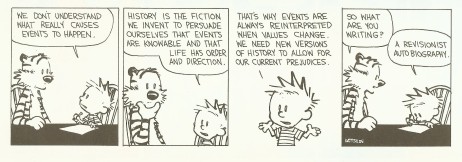

Today, we tend to think of autobiographies (even best-selling ones) as personal and private accounts, designed to give us an insight (or the illusion of an insight) into the minds and motives of the writer. As Lynch puts it, ‘As modernists, we seek individualism in autobiography. In early modern narratives, we find only a tenuous alignment of authorship as we understand it and first-person testimony’ (23). Looking at conversion narratives, then, pushes us to think again about how we understand ‘authorship’ and how we conceptualise the different meanings and purposes of acts of repetition, witnessing, and testimony that are central to social and political life.

The texts that Lynch studies were personal testimonies in one sense, and required converts to think back over their own life histories in order to fit them into an established narrative pattern. As Lynch points out, however, these stories followed a strict, and highly repetitive format, and their purpose was less to reveal the workings of the individual conscience than to build a collective religious and political identity.

Seventeenth-century conversion narratives were, Lynch suggests, ‘teleological’ in form (directed towards a highly specific end). Lynch argues persuasively that we need to study ‘self-representational truths in a nexus of trade and regulatory environments’ (24), and to ask how accounts which present themselves as transparently ‘truthful’, thanks to their first-person voice and personal testimony, are shaped by — and help to shape — the contexts in which they are produced. In these examples, Lynch suggests, we can see how conversion narratives have much wider resonances, are crucial to ‘social as well as personal identity’, and articulate ‘a highly dynamic interplay of individual and communal identity’ (30).

Lynch draws on Philippe Lejeune’s influential idea of ‘the autobiographical pact’ — the silent treaty made between an autobiography and its readers. Readers expect the author’s name on the cover to match the proper name of the person who is writing, and the person who speaks in the first person throughout the text.

For Lynch, a text’s appearance in print is part of the pact between readers and writers: from the title-page onwards, these books ask readers to enter into the spirit of the congregation and to receive these texts as testimonies of authentic religious experiences. Protestant Autobiographies is unusual — and important — in thinking carefully about how these texts were presented to their readers, and how their changing forms produced new understandings. Knowing what texts looked like and how they circulated is essential, Lynch argues, because ‘crucially, for autobiographical writing, textual histories constitute the material traces by which a life is understood, prosthetically extended, and made available for imitation’ (12).

In her final chapter, on the dissenting Puritan theologian Richard Baxter, Lynch uses Baxter’s ongoing process of life-writing, and his refusal or inability to publish his own spiritual autobiography as a way of highlighting the complex politics of writing the religious self within a shifting political climate. In a way, we have come full circle, back to Donne’s reluctance to present his religious experiences as constitutive of his self, though Baxter’s highly polemical writings consistently elevate the soul above the state.

Lynch acknowledges that ‘writing has a prosthetic relationship to the self’ (it is at once part of us, and something which extends us into the world), but insists that the relationship between self and writing is neither simple nor stable (257). Writing and rewriting books, she argues, is a process of ‘writing and rewriting of self’.

What Lynch’s book finally presents us with is a sense that firm conclusions are hard to reach: whilst we like to think of conversion as a secure state or a definable moment, the accounts that Lynch analyses in compelling detail suggest selves in flux, continually seeking definition, and continually failing to fully resolve the multiple contradictions of experience. The self presented in these texts is a communal endeavour, one brought into being in part by the individual conscience, but in much larger part by the relationship of the individual to existing narrative models, to communities of like-minded (or distinctly not like-minded) believers, and to the inextricably linked politics and religion of the early modern Atlantic world.

A very intriguing read! Lynch’s discussion of sprirtual accounts as communal productions reminded me of Natalie Zemon Davis’ exploration of the construction and fictional qualities of remission letters in which numerous people were often involved in a texts composition. This could therefore place these spiritual accounts into wider discussions concerning practices of textual production and the way in which texts were culturally patterned.